An Introvert as Activist

Introverted activists who successfully agitated for social change include Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt, Rosa Parks – and tireless women’s suffrage advocate Susan B. Anthony.

For 45 years she gave 75 to 100 speeches per year, all over the United States as well as in Europe. When it was considered scandalous for a woman to show up, let alone stand up, at a public meeting, neither hecklers nor skeptics cowed her from speaking out in favor of the vote for women. Convinced that the US Constitution’s phraseology of “citizens” included women, she cast a vote in the presidential elections of 1872, for which she was arrested, tried, convicted and fined $100. She never paid.

At age 86, when President Theodore Roosevelt sent her a congratulatory telegram at a meeting celebrating her birthday, she rose in indignation, blasting him for failing to prod Congress to act on the cause that remained her single-minded objective. Only after her death did the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution finally grant women the right to vote. In recognition of the paramount role she played in bringing about this historic event, she later became the first woman (not counting Lady Liberty) to have her portrait cast onto an American coin.

Does this sound like an introvert? Only when we fill in other aspects of her story.

Susan B. Anthony as an Introvert

Born in 1820 near Mount Greylock in the northwest corner of Massachusetts, Susan Brownell Anthony grew up in a Quaker family. Although her father married a non-Quaker, he instilled in his children values typical of that austere Protestant denomination: simplicity, temperance (not drinking alcohol), the importance of freedom from slavery for African-Americans, the equality of all humans, and heeding messages from one’s inner voice. We can detect the influence of that upbringing in Susan’s outsized dedication to rights for women and her lifelong dread of “fuss and ceremony.” But the tenacity and style with which she pursued those values were her own.

What comes through consistently while reading about her now is that she was driven by principle. The words “unjust,” “unreasonable,” “justice” and “equality” crop up over and over again in her speeches. Anthony saw something wrong and simply had to do something about it. She earnestly used facts and logical arguments – not appeals to emotion – to sway listeners, convinced that if she kept up this rational onslaught, opponents would have to concede that she was correct. Indeed, one reporter said that any men in her audience would “slink out after the lecture, looking very much as though they had been well whipped.”

In all this she reminded me of today’s young climate activist Greta Thunberg, also an introvert, who tries to goad the leaders of the world into taking action and goes to great lengths to sidestep hypocrisy when she travels to speak. “This is all wrong. I shouldn't be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean,” Thunberg told the United Nations in 2019.

Likewise, observers who attended Susan B. Anthony’s lectures perceived that she cared only about making her case, not about raising her standing in the eyes of the audience. She always wore black to speak, so as not to distract from her message. In the words of a journalist from Indiana:

Miss Anthony has something to say, and she says it decidedly, positively; and her earnestness is stronger than the most conspicuous eloquence. She depends more upon solid and strong argument than elegant diction. She takes her position on the stage in a plain and unassuming manner and speaks extemporaneously, and fluently too. She clearly evinced a quality that many politicians lack – sincerity.

When she did use rhetoric to sway listeners or readers, it was witty, easily understood analogies. In response to the objection that most women did not want the vote, for instance, she said: “Then why do men put the words ‘white males’ into their Constitutions? Men don’t fence a corn field because the pigs don’t want the corn. They fence the field to keep the pigs out.” At a Congressional hearing she stingingly retorted to same objection, “The majority of children are against public schools, but we put children in public schools all the same.” Other times, she used opponents’ very principles against them, as when she echoed the slogan of those who had rebelled against British rule. She now applied the slogan to women: “Taxation without representation is tyranny.”

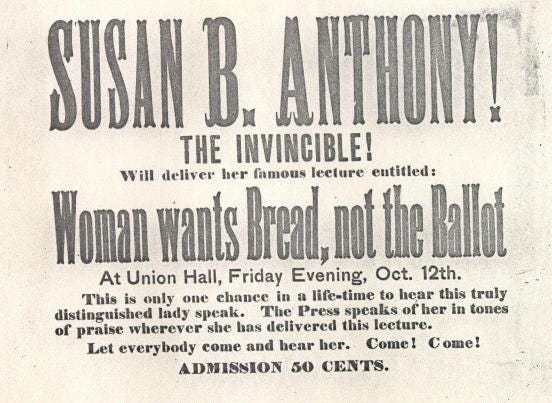

Although Anthony’s relentless public efforts might seem contrary to the temperament of an introvert, keep in mind that she agitated in order to accomplish something in line with her deep, unshakeable convictions. Personal glory or social admiration meant nothing to her. I wish I could have been there in an Oregon hall in 1871 when she spent two and a half hours refuting one by one arguments that had been submitted ahead of time, dispatching each with “ready ingenuity and plausibility,” as a reporter put it. Only an introvert would have had the stamina for this type of virtuoso performance. Yet I’m certain that if women’s suffrage had been achieved in her lifetime, Susan B. Anthony – “The Invincible,” as she was touted in ads for her lectures – would most likely have finally relaxed.